I’ve never cried while watching a surf contest. I’ve been thrilled a few times, angry lots of times, and I’ve been bored more times than I’d like to admit. But I’ve never had a tear well up in my eye in the process of viewing people in colored singlets attempting to outsurf one another. Hadn’t, at least, until today.

After competing in hundreds of amateur and pro events, covering dozens of others on the world tour, and watching as a fan forever, suddenly, today, tears. Do you want to know when someone cries at a surf contest?

When you see a six-year-old kid learning to surf at The Jetty with his dad, getting pushed into whitewaters as you ride into the shorebreak.

When that kid is 14 and he comes to your Sunday morning surf training, and you give him a few tips but can’t tell him the one thing holding him back, that’s he’s a scrawny kid and just needs time to fill out.

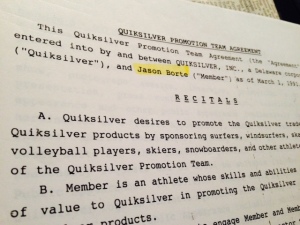

When the kid is 18 and starts traveling all over creation and immersing himself with good surfers and good waves and slogging his way through the trials and tribulations of international competition, a many year process, during which he may as well be in witness protection because he’s buried so deep in the ranks.

When he is 20 and you watch random events online, where the kid is surfing crazy fast but is still scrawny and unconfident, not unconfident in his ability, but unconfident in whether it is okay for him to knock off the best surfers in the world, even though he’s surfing better than they are.

When he is 24 and you tune in online and see that this year is different because the scrawny kid is filling out and gets pissed when he loses to the best surfers in the world, because he should be beating them and he knows it.

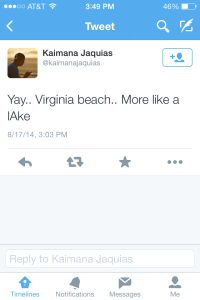

When the kid comes home to the event that hasn’t been won by a kid from The Jetty since 1981, the year before you started surfing, and you’ve surfed this event countless times, made the finals a handful of times, once even came in and were told you won and were chaired up the beach on the shoulders of the guy who won back in ’81, but you ended up in second and had to watch another guy from Florida, or California, or Brazil, or New Jersey somehow finish on top and you feel like you let people down and you wonder if a local surfer will ever break through.

When you pedal to the beach to watch the kid’s first heat yesterday, and you track him down before he paddles out to assure him, You got this.

When you catch the rest of his heats online, heats in which he is fast, but also cool, radical, powerful, and dominant.

When he knocks out last year’s champ on the way to the final.

When he’s losing the final until the waning minutes and he scorches another jetty right that eliminates all doubt.

When the final horn blows and the kid enjoys a victory lap with his arms raised in elation.

When his friends don’t wait for him to hit the sand but rush into the water and hoist him onto their shoulders.

When that ’81 champ carries the kid’s board behind them and the entire procession has stoke shooting from their pores like fireworks.

When the beach screams with something it hasn’t been able to scream with in forever, something like pride.

When you feel that pride coursing through your veins and it causes the skin on your arms to erupt into little bumps and the hairs to stand at attention.

When the look on that kid’s face is the greatest look ever invented, that of pure joy.

When that stuff happens, your eyes get a little moist. Tears aren’t running down your cheeks, not like when you watch Rudy, but you can feel the moistness. You know that you had a little something to do with what is unfolding, just a tiny bit, because that kid once looked at you and said, It can be done. And he went out and did it.

And you know what you do then? You do something you haven’t done in years. You go down to a bar on the strip at almost midnight, even though you have to start school early the next morning, and you walk into that bar and see a mass of people toward the back. It isn’t the normal mass of people, downing drinks to try to forget that some out-of-towner swooped in and looted the top prize. This mass of people is celebrating.

You make you way into the middle of the mass because the kid is in there somewhere. You find the kid and he’s still coherent. His eyes light up. He’s honored that you made this effort. You’re honored that he’s honored. You lean in towards the kid and you say, You’re the man. And you step back to let everyone else tell him. And you walk out of that bar with your faith restored because it only took you 30 years to prove that good things can come from surf competition.